Ghani Khan Baba(Born1914–1996)

Ghani Khan Baba(Born1914–1996)(Pashto: غني خان) was a Pashto language poet, artist, writer, politician and Philosopher of the 20th century. He was a son of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan and older brother of Khan Abdul Wali Khan.

Khan Abdul Ghani Khan was born in Hashtnagar in the then North-West Frontier Province of British India, or the modern-day village of Utmanzai in Charsadda District, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. He was the son of the Red-Shirt Leader Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan and elder brother of Khan Abdul Wali Khan. His wife Roshan came from a Parsi family and was the daughter of Nawab Rustam Jang. He went to study at the art academy at Rabindranath Tagore’s university in Shantiniketan and developed a liking for painting and sculpture. He visited England and studied sugar technology in the United States, after which he returned to India and started working at the Takht Bhai Sugar Mills in 1933. Largely owing to his father’s influence, he was also involved in politics, supporting the cause of the Pashtuns of British India. He was arrested by the Government of Pakistan in 1948 – although he had given up politics by then – and remained in prison till 1954, in various jails all over the country. It was during these years that he wrote his poem collection Da Panjray Chaghaar, which he considered the best work of his life. His contribution to literature (often unpublished) was ignored by the Pakistan government for much of his life although near the end of his life his works did receive much praise and as well as an award from the Government of Pakistan. For his contributions to Pukhto literature and painting, the President of Pakistan, General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, conferred on him the prestigious award of Sitara-e-Imtiaz (23 March 1980).

Ghani Khan's love for nature and the local habitat of the Pashtun people is visible in his work. He wrote

"Pashtun is not merely a race but, in fact, a state of mind; there is a Pashtun lying inside every man, who at times wakes up and overpowers him."

"The Pashtuns are a rain-sown wheat: they all came up on the same day; they are all the same. But the chief reason why I love a Pashtoon is that he will wash his face and oil his beard and perfume his locks and put on his best pair of clothes when he goes out to fight and die."

As a progressive and intellectual writer, he wrote, "I want to see my people educated and enlightened. A people with a vision and a strong sense of justice, who can carve out a future for themselves in harmony with nature."

After his death, in recognition of his outstanding achievements, the Government of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa Province built a public library and park as a memorial to him on about 8 acres (32,000 m2) of land, naming it "Ghani Derai" (the mound of Ghani). The site is an historical mound very near his home, Dar- ul-Aman, and within the confines of his ancestral village, Utmanzai, on the main highway from Razzar to Takht-i-Bhai.

Education

Much of Ghani Khan’s poetry is about the mullah, the religious leader, the clergy. An understanding of his conversations with these mullahs in his poetry requires an understanding of Ghani Khan’s upbringing and his education. And so we proceed.

Ghani Khan received his early education from a religious leader/teacher in the village local mosque; this was, and still is, a custom in many parts of the Muslim world, including Pashtunkhwa. Later on, however, he was sent to the National High School in Peshawar city and then later to the Azad (Free) School in Utmanzai, which was founded in 1921 by his father, Bacha Khan, with the assistance of the Anjuman-e-Islah-ul-Afaghina (Society for the Reformation of the Afghans). Here, he became proficient in Arabic and Urdu and passed the Punjab University Matriculation in 1927. He afterwards studied in the Jamia Milli (National College), Delhi, a Muslim religious institution founded in 1920 for the study of the traditional Islamic thought. Bacha Khan removed him from the institution in 1928, however, because of the clergy’s revolts against Amanullah Khan, who was the liberal, progressive Emir/King of Afghanistan (1919-1929) who wanted to modernize Afghanistan.

Ghani Khan received his early education from a religious leader/teacher in the village local mosque; this was, and still is, a custom in many parts of the Muslim world, including Pashtunkhwa. Later on, however, he was sent to the National High School in Peshawar city and then later to the Azad (Free) School in Utmanzai, which was founded in 1921 by his father, Bacha Khan, with the assistance of the Anjuman-e-Islah-ul-Afaghina (Society for the Reformation of the Afghans). Here, he became proficient in Arabic and Urdu and passed the Punjab University Matriculation in 1927. He afterwards studied in the Jamia Milli (National College), Delhi, a Muslim religious institution founded in 1920 for the study of the traditional Islamic thought. Bacha Khan removed him from the institution in 1928, however, because of the clergy’s revolts against Amanullah Khan, who was the liberal, progressive Emir/King of Afghanistan (1919-1929) who wanted to modernize Afghanistan.

Bacha Khan had initially intended to make an alim, religious scholar, out of Ghani Khan. But the revolts against and the removal of King Amanullah deeply disappointed Bacha Khan, and he thus decided to send Ghani Khan to England to receive Western education. Ghani Khan thus left for England when he was fifteen years old. Bacha Khan later arranged for Ghani Khan to be sent to the U.S. for education because he was not satisfied enough with Ghani’s British education. Afghanistan’s ambassador to the UK at the time sent him to the U.S. to study sugar technology at the University of Southern Louisiana. Unfortunately, in 1931, Bacha Khan, along with many other prominent congressmen, was arrested for “civil disobedience,” and their properties were restrained, leading to financial troubles for Ghani’s family. He therefore left the U.S. without completing his education–but he nonetheless worked in Takht Bhai Sugar Mills near his hometown in 1933. After his return from the West, he was highly influenced by Western lifestyle and attitude. Bacha Khan was displeased to see this, fearing that Ghani had lost respect and love for his culture, civilization, and history; as a result, Ghani was sent to Allahabad (India), where he stayed for eight months with Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964), an Indian politician and later the first Prime Minister of Independent India who treated and loved Ghani Khan like his own child.

In December 1934, Ghani Khan went to Bombay where, at a friend’s house, he met and fell in love with Roshan (1907-1987), a Parsi lady of noble birth. [Parsis are a Zoroastrian community that migrated from Iran in the 10th century after the Islamic conquest and settled in India where they adopted Gujarati as their language.] After six years of courtship, she finally consented and married him on November 24th 1939. A well-educated lady of great beauty, culture, and sophistication, she brought almost six thousand books with her and was very supportive of Ghani’s artistic inclinations. She bore him two daughters, Shandana and Zareena, and a son, Faridoon. Faridoon died in 1987, about a decade before Ghani’s own death.

Due to some personal and intimate issues, Roshan went to India and returned only after Ghani Khan promised to “behave.”

Political Life and Imprisonment

During a part of Ghani Khan’s life, modern-day Pakistan did not exist. India was under British rule (hence called British India) and was fighting for its independence from the British. On August 15, 1947, India finally gained its independence. And a day before, on August 14th 1947, Pakistan had been born, becoming independent of British India. Hence, before all this independence, the Pashtuns who are now in Pakistan (all except the Swati Pashtuns, since Swat was an independent, princely state until 1964) were under the rule of British India before the partition of India and Pakistan. This is where and why Bacha Khan’s work was significant.

As for Ghani Khan, he was initially influenced by his father’s political struggles and thus worked for the independence of the Pashtuns ruled by British India. However, he later came to disagree with his father’s ideologies (he stopped supporting the idea of non-violent resistance, seeing that it was not beneficial to the Pashtuns). He says, in an interview, that he left his father’s political movement of non-violence, called “Khudai Khidmatgar” (“God’s Soldiers”) because of some of the movement’s motives that he disagreed with.

I left his [his father’s] [Khudai Khitmatgar] Movement and came and sat at home. He wanted me to become President of the Movement. I said no. He sent me all sorts of people but I said I will not do it. I had had a fight with him. I did not agree with his program. I am a bit of a socialist. I begged him to make an economic program. I told him Sir, there are eighty steps between communism and conservatism. Stand anywhere, choose any mixture, either way, nearer communism nearer conservatism, wherever you like but stand somewhere for heavens sake, and say this is my stand on economics. All these boys, I mean all the fellows who went with him to jail, their grandsons have passed BA and MAs in economics and political science. They keep on asking what is your economic program? And he said nothing.

Although he was no longer involved in politics by the time of Pakistan’s independence (1947), the government of Pakistan imprisoned him several times, sending him to jails from all over the country. His father spent close to half of his lifetime in jail (44 years out of his 99 years!). Ghani Khan used his time in jail to write poetry; his main work in jail is called Da Panjrey Chaghar (“The Chirping of the Cage”).

Literary Work

Ghani Khan wrote extensively on all subject matters. His first book was published in English in 1947 and is titled The Pathans, available online here; the book is a humorous and delightful sketch of the Pashtuns, covering virtuallly all aspects of their life–their social customs and practices, their superstitions, their enmities, their attitudes on life.His next book was published in 1956, entitled Da Panjray Chaghar (“The Chirping of the Cage”), contains poems written between October 15, 1950 and October 27, 1953 when he was imprisoned.Hisother books are: Palwashay (“Beams of Light”), which includes poems from his early book as well as some new ones; Panoos (“Chandelier”) consists of selections from the earlier works and a number of new poems, published in 1978. In 1985, Kulliyat(“Collected Works”), a compendium of his published verses, appeared. Ten years later, in 1995, Latoon (“Search”), containing all of his poems published to date, including some new ones, was published. His poetry was written primarily in Pashto. The book he wrote in Urdu is Khan Sahib (on his father), published in 1994. As mentioned earlier, much of his poetry is about the mullah (the religious leader), whom he calls “Mula Jaan” (the beloved mullah). One of my personal favorite poems of his, sung by Sardar Ali Takkar, a highly respected Pashto singer, is called “Mula Jaan Wayi Azal Ke” (“The mullah tells us that from the very beginning …”). An English translation of this song/poem can be found here (bottom of page), along with the Pashto script of the poem as well as the transliterated. Another of his poems, with a similar theme (religion, philosophy, God), is called “Lord My Beloved” (also “Heaven and Hell”), a rough Pashto translation of his “Che masti we ao zwani wi” (“if only fun and youth were eternal!”). For an English translation of some of his poetry, as well as for some of his other works, please click Ghani Khan: Life and Works of Ghani Khan. [I will write about his poetry in another post, so as to avoid making this post too long. Thank you for your patience.]

Ghani Khan wrote extensively on all subject matters. His first book was published in English in 1947 and is titled The Pathans, available online here; the book is a humorous and delightful sketch of the Pashtuns, covering virtuallly all aspects of their life–their social customs and practices, their superstitions, their enmities, their attitudes on life.His next book was published in 1956, entitled Da Panjray Chaghar (“The Chirping of the Cage”), contains poems written between October 15, 1950 and October 27, 1953 when he was imprisoned.Hisother books are: Palwashay (“Beams of Light”), which includes poems from his early book as well as some new ones; Panoos (“Chandelier”) consists of selections from the earlier works and a number of new poems, published in 1978. In 1985, Kulliyat(“Collected Works”), a compendium of his published verses, appeared. Ten years later, in 1995, Latoon (“Search”), containing all of his poems published to date, including some new ones, was published. His poetry was written primarily in Pashto. The book he wrote in Urdu is Khan Sahib (on his father), published in 1994. As mentioned earlier, much of his poetry is about the mullah (the religious leader), whom he calls “Mula Jaan” (the beloved mullah). One of my personal favorite poems of his, sung by Sardar Ali Takkar, a highly respected Pashto singer, is called “Mula Jaan Wayi Azal Ke” (“The mullah tells us that from the very beginning …”). An English translation of this song/poem can be found here (bottom of page), along with the Pashto script of the poem as well as the transliterated. Another of his poems, with a similar theme (religion, philosophy, God), is called “Lord My Beloved” (also “Heaven and Hell”), a rough Pashto translation of his “Che masti we ao zwani wi” (“if only fun and youth were eternal!”). For an English translation of some of his poetry, as well as for some of his other works, please click Ghani Khan: Life and Works of Ghani Khan. [I will write about his poetry in another post, so as to avoid making this post too long. Thank you for your patience.]

Importantly, one of my most favorite poems of his that’s been converted into a song is sung so beautifully by a Pashto singer named Saima Naz. Check it out; it’s called Stargo Da Janan Ke Zama Khkuli Jahanona De – it’s a message to God, sort of, where The Ghani says, “Feel free to take back your world; I’ve a much more beautiful world in front of my when I look into my beloved’s eyes!” #dies

Personal and Later Life

As mentioned above, his son Faridoon pre-deceased him. He died On October 6th, 1987 due to liver problems. On December 22nd 1987, Roshan, his wife of over four and a half decades whom he loved deeply and passionately, passed away due to heart failure. He became lonelier than ever before, but the births of his grandchildren managed to take some of the loneliness away–although his close friends said of him that he was never the same after his wife’s death. Ghani Khan died on March 15th 1996 and was buried the next day, next to his mother in his ancestral graveyard outside their village. People from all over the province, the Tribal Areas, Baluchistan, and Afghanistan attended his funeral, and his death was widely mourned as the passing away of a great poet, painter, sculptor, and leader. Then-president Farooq Ahmad Khan Leghan and then-Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto visited Ghani Khan’s village to give condolences to his family.

As mentioned above, his son Faridoon pre-deceased him. He died On October 6th, 1987 due to liver problems. On December 22nd 1987, Roshan, his wife of over four and a half decades whom he loved deeply and passionately, passed away due to heart failure. He became lonelier than ever before, but the births of his grandchildren managed to take some of the loneliness away–although his close friends said of him that he was never the same after his wife’s death. Ghani Khan died on March 15th 1996 and was buried the next day, next to his mother in his ancestral graveyard outside their village. People from all over the province, the Tribal Areas, Baluchistan, and Afghanistan attended his funeral, and his death was widely mourned as the passing away of a great poet, painter, sculptor, and leader. Then-president Farooq Ahmad Khan Leghan and then-Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto visited Ghani Khan’s village to give condolences to his family.

Ghani Khan’s Epitaph

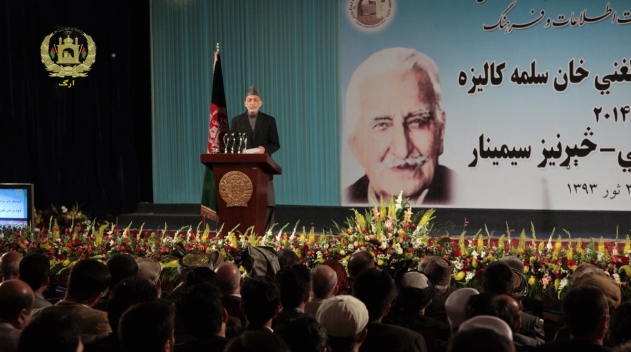

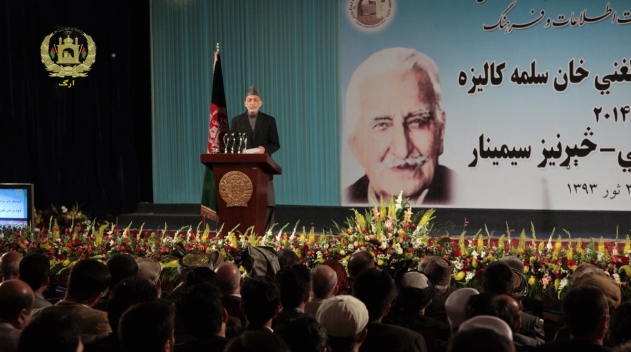

Ghani Khan is considered (and indeed he is!) one of the most brilliant, most respected Pashto poets and thinkers in Pashtun history. In May 2014, according to The Kabul Times, the former president of Afghanistan, Hamid Karzai, “inaugurated the seminar on the 100th birthday anniversary of great Pashto poet Ghani Khan at the hall of national radio and television on Thursday. In his remarks the president said, ‘The environment where Ghani had grownup had great impact on his poetry’ saying Ghani khan’s poetry is the outcome of the environment where he used to live. His sense, political views, loving life is the outcome of the place he used to live.”

On March 23, 1980, General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, Pakistan’s president from 1978-1988, granted him the prestigious award of Sitara-e-Imtiaz (Star of Excellence) for his contributions to Pashto literature and painting. Additionally, the Government of Khyber Pashtunkhwa Province has built a public library and park as a memorial to him on about eight acres of land; it is called Ghani Derai (the mound of Ghani). The site is a historical mound built close to his home, encircling his ancestral village of Utmanzai on the main highway. At least three books about him have been published after his death. One is Ghani Khan: A Poet of Social Reality by Arif Khattak. The other is Strains of Romanticism in Abdul Ghani Khan and John Keats (Poetry, A Comparative Study) by Shazia Babar, who wrote her PhD dissertation on Ghani Khan’s and John Keat’s poetry, noting the similarities between the two poets’ philosophies and styles. In 2009, the book “Ghani Khan- Da Pukhto Adab da Shalami Sadai Shakhsiat (Pashto, “Ghani Khan – The 20th Century Pashto Literary Figure”) was published; it is “a thesis by late Fazli Ghani Ghani, the eminent Pashtun writer who was killed when a suicide bomber targeted the house of Asfandyar Wali Khan on October 2, 2008,” Muhammad Zai Khan writes on his blog.

And, oh yeah, about a year ago, I wrote a poem in his name entitled “Weeping at Ghani’s Grave.” Yes, I do feel like the tribute of little fans like me counts, too.

Ghani Khan has several interviews on Youtube. This is a good one to start with to hear him talk: Khan Abdul Ghani Khan Interview, Part I.

Then there are also interviews conducted with Sardar Ali Takkar, an influential contemporary Pashto singer who sings Ghani Khan’s poetry with a mesmerizing melodious voice. In this short clip, Takkar tells us that Ghani Khan told him that he swears they complement each other perfectly: Ghani’s words sung in Takkar’s voice. I had intended to include my personal thoughts on Ghani Khan in this post. I wanted to share with my readers what happens to my mind when I think of him, when I listen to his poetry, when I read him … I wanted to sketch to you all that smile that is almost permanent on my lips because of Ghani Khan. It’s the kind of smile that no grief, no sorry has the power to remove. I wanted, also, to discuss his poetry, the themes of his poetry, their meaning, their power, their wisdom. I want to go into details discussing Ghani’s understanding of God and religion as I understand from his poetry alone. But this post has gotten long enough already, so I’ll have to talk about that in another blog post.

Then there are also interviews conducted with Sardar Ali Takkar, an influential contemporary Pashto singer who sings Ghani Khan’s poetry with a mesmerizing melodious voice. In this short clip, Takkar tells us that Ghani Khan told him that he swears they complement each other perfectly: Ghani’s words sung in Takkar’s voice. I had intended to include my personal thoughts on Ghani Khan in this post. I wanted to share with my readers what happens to my mind when I think of him, when I listen to his poetry, when I read him … I wanted to sketch to you all that smile that is almost permanent on my lips because of Ghani Khan. It’s the kind of smile that no grief, no sorry has the power to remove. I wanted, also, to discuss his poetry, the themes of his poetry, their meaning, their power, their wisdom. I want to go into details discussing Ghani’s understanding of God and religion as I understand from his poetry alone. But this post has gotten long enough already, so I’ll have to talk about that in another blog post.

Thank you for reading! Stay tuned for more Pashtun Personalities.

Sources:

An Interview with Ghani KhanGhani Khan Baba (the above is pretty much a shorter and altered version of the biography on this page. I have pasted some of the lines verbatim, and all credit goes to those who wrote the original biography. Many thanks from the qrratugai!)

On March 23, 1980, General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, Pakistan’s president from 1978-1988, granted him the prestigious award of Sitara-e-Imtiaz (Star of Excellence) for his contributions to Pashto literature and painting. Additionally, the Government of Khyber Pashtunkhwa Province has built a public library and park as a memorial to him on about eight acres of land; it is called Ghani Derai (the mound of Ghani). The site is a historical mound built close to his home, encircling his ancestral village of Utmanzai on the main highway. At least three books about him have been published after his death. One is Ghani Khan: A Poet of Social Reality by Arif Khattak. The other is Strains of Romanticism in Abdul Ghani Khan and John Keats (Poetry, A Comparative Study) by Shazia Babar, who wrote her PhD dissertation on Ghani Khan’s and John Keat’s poetry, noting the similarities between the two poets’ philosophies and styles. In 2009, the book “Ghani Khan- Da Pukhto Adab da Shalami Sadai Shakhsiat (Pashto, “Ghani Khan – The 20th Century Pashto Literary Figure”) was published; it is “a thesis by late Fazli Ghani Ghani, the eminent Pashtun writer who was killed when a suicide bomber targeted the house of Asfandyar Wali Khan on October 2, 2008,” Muhammad Zai Khan writes on his blog.

And, oh yeah, about a year ago, I wrote a poem in his name entitled “Weeping at Ghani’s Grave.” Yes, I do feel like the tribute of little fans like me counts, too.

Ghani Khan has several interviews on Youtube. This is a good one to start with to hear him talk: Khan Abdul Ghani Khan Interview, Part I.

Thank you for reading! Stay tuned for more Pashtun Personalities.

Sources:

An Interview with Ghani KhanGhani Khan Baba (the above is pretty much a shorter and altered version of the biography on this page. I have pasted some of the lines verbatim, and all credit goes to those who wrote the original biography. Many thanks from the qrratugai!)

0 Comments